- Home

- Sharon Rechter

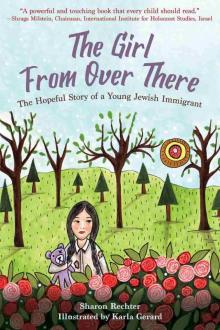

The Girl From Over There

The Girl From Over There Read online

Copyright © 2020 by Sharon Rechter.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Sky Pony Press books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Sky Pony® is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Kai Texel

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-5367-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-5368-6

Printed in China

In honor of my grandparents the beloved Meir & Irena Rechter, and Blanka & David Lavie who were the inspiration for this book.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

We were sitting on the big lawn, making plans for the upcoming Hanukkah party, when she popped up from behind the rosebushes. She seemed unsure about whether she should come out of her hiding spot, but once she realized we were all looking at her she came out. Two long, black braids framed a frightened face with big brown eyes. She looked about our age, eleven or so, and she was clutching a tattered, purple teddy bear to her chest. She stood up straight, and though a fiery sort of bravery burned in her eyes, there was fear in them too. Her old dress, once white, was now gray from grime and wear.

As she stood there, we—the children of the kibbutz1—stared at her in wonder, puzzled by her disheveled dress and, given her age, the faded teddy bear in her hands. She looked at us, too afraid to come any closer, so we simply sat there, judging, aiming somewhat condescending looks at her appearance, which was both confusing and amusing at the same time.

She kept her frightened eyes fixed on us for another minute or two.

I wondered, Did she want us to invite her to join us? Or was she scared of us?

Then, in a flash, she ran for her life. We immediately abandoned our party preparations and began to chatter among ourselves. Who was she? Where had she come from? Would she stay? Her clothes were so weird; where were they from? Was she from over there? We’d heard, after all, that barely any children had made it from over there. Was she alone? Where were her parents? Did Leah, the caretaker,2 know about her? She was new. That much we knew for sure.

We hated her instantly, but no one could say why. She was just different, and she didn’t belong. What kind of a girl wore a dress on the kibbutz, and a dress like that one, so narrow and worn-out? And who, at our age, still carried around a stuffed animal? Maybe that was why she seemed so different to us.

Our thoughts were cut short by Joel, who called us to the dining hall.

Even though we were a small kibbutz, at lunchtime our dining hall was bustling with children, families, toddlers, all speaking at once, creating a loud mix of laughter and heated discussions about daily news and kibbutz gossip. And since it was my turn to serve food to the kibbutz members, the new girl completely slipped my mind.

After lunch, the other members returned to their duties, and I stayed behind to clean up and clear the tables with Abigail, Yael, and Gili, the other girls on dining hall duty that day. Naturally, our conversation found its way back to the girl we had seen that morning.

“Did you see her?” Gili asked.

“See who?” Yael replied.

“The girl with the teddy bear.”

“Of course I did,” I said.

“So, what do you think about her?” Gili asked condescendingly.

“I think she wanted to sit with us,” Abigail said.

Then Gili added, “I bet she’s from over there.”

“Why do they keep sending them all here, to our kibbutz?” Yael asked resentfully.

“She’s probably all alone,” I pondered out loud.

Abigail asked mockingly, “So, Michal? Do you feel sorry for her?”

“No way,” I said, snapping out of my daydream. To emphasize this, I added, “As far as I’m concerned, she can go to hell!”

“You know, they say they’re different,” Gili added.

“What do you mean different?” I asked, as if trying to find the reason I felt so disgusted by her.

“Oh, please,” Yael said. “Can’t you tell? They’re so weird.”

She made a face as she said this, sending a wave of laughter through us.

“All of them?” asked Abigail.

“Yes,” Yael said knowingly. “They’re all the same. They’re cowards, and they’re weird, and they hold on to old things like some precious treasure. And they always hold back their tears like heroes.”

“Shh,” Gili whispered. “Leah’s coming over with her.”

We fell silent and turned back to our work. Leah opened the door. “Hello, girls,” she said kindly.

“Hello,” we answered in a chorus.

“Girls, this is Miriam. She’s new to the kibbutz, and she’s come to us from far away. Let’s make sure she’s happy here with us.”

An awkward chuckle rippled through our group.

Leah walked over to me. “Michal, dear, is there anything left to eat?” she asked.

“Yes,” I answered. “It’s all in the kitchen.”

Leah walked into the kitchen, leaving behind the frightened girl with the teddy bear in her arms. We all turned to stare at her.

Abigail whispered to me, “She doesn’t look that weird or different to me. Maybe she is a little bit …” Abigail was searching for the right word when Yael cut her off.

“Would you like to see a rabbit?” Yael teased, her eyes glancing back and forth between us and the skinny new girl, who was ready to retreat at any moment.

Without waiting for an answer, Yael walked up to her and asked, “Are you from over there?”

The girl said nothing.

“Are you from over there?” Yael repeated her question with force.

“She’s not answering,” Abigail said. “Leave her alone.”

“She’ll answer me,” Yael cried out, and pulled hard on Miriam’s braid.

Miriam gasped in pain, her eyes pleading. But she did not open her mouth.

“You see, I told you. They hold back their tears like heroes and act like they’re all perfect,” Yael said, proud of herself. She let go of the girl’s braid. Free of Yael’s grasp, she fled. Unsettled by Yael, we returned to our jobs in silence.

A few minutes later, Leah stepped out of the kitchen and asked, “Girls, where is she?”

“She left,” Yael said. An evil glint burned in our eyes.

Chapter 2

That evening, Leah walked Miriam to our communal bedroom.3 There she was, the “weird girl,” still clutching her ever-present teddy bear.

Abigail, Gili, Yael, and I exchanged quick glances. We were scared that Miriam had told Leah about what had happened in the dining hall, and we braced ourselves for our punishment. But Leah didn’t say a word about it. Was it possible she’d decided to ignore it? Or maybe … maybe she knew nothing about it.

Leah spoke in her motherly tone and said, “Girls, I’d like you to meet Miriam. She came here all the way from Poland. Miriam is an orphan; she has no mother and no father—just a little brother, who is five years old.”

Gili whispered to me, “You see? She is from over there!”

“Please make her feel welcome,” Leah continued.

“Oh, we will!” Yael muttered, and I smiled.

“She’s been through a terrible war. I know there might be times when you think she’s a bit odd.” Hearing this, Abigail giggled, trying to hide her smile behind my back. “But you must understand, children, that she’s just going through a difficult time. This is a new place, with a different language, and her memories are very painful.”

Leah proceeded to tell us about the horrific war that had just ended in Europe and the Nazi persecution of the Jews. We weren’t listening, as it seemed so far away. We’d heard these things before from immigrants, both legal and illegal.4 Nathan, who’d arrived just a few weeks ago, would tell all the children his story every chance he got. But, to be honest, we had yet to meet a girl from over there.

Leah finished her introduction and showed Miriam to her new bed. Our stares were so aggressive—so menacing—as we watched her that I’m sure she must’ve felt it.

Leah placed Miriam’s meager personal belongings, which were packed in a loose bundle, into a wooden cubby. Is that really all of her stuff?, I wondered. They exchanged a few words; Leah spoke, and Miriam nodded. When she was done, Leah stood up straight, looked at us, and said, “Miriam only knows a few words in Hebrew, and will need some help, so I would like to ask one of you …” Leah paused. It was as if she was measuring the room, seeking a pair of kind eyes, a glimpse of generosity, but she didn’t find it. All eyes were avoiding her, focused on an unseen mark on the floor. She continued, asking someone to please help Miriam. Her voice was assertive, yet I could now hear some disappointment in it, too.

Leah continued to look around, a frown on her face as she waited, but the room was deadly silent. No one wanted to volunteer.

Suddenly, Dan took a single step toward them, saying, “I’ll help her.”

His eyes were kind, his voice warm. I felt a pinch in my heart.

It was then that I noticed that Dan’s bed was right across from Miriam’s bed, and I felt my anger toward Miriam bubble up once again. Dan was my boyfriend. I was suddenly afraid she’d take my place with him, and at that moment I justified Yael’s cruel prank and even took pride in it.

I can’t remember the rest of that night. I was so anxious about the “new girl” that I paid no attention to anything else around me. I’m sure the other kids eventually got into their beds, and Leah turned out the lights, just like normal, but I honestly have no memory of it. I was so worried that I couldn’t sleep all night.

The next day, just as I expected, Miriam became the center of attention at the kibbutz; the grown-ups fretted over her, brought her gifts and candy, and peppered her with question after question, just in case she knew anything about the fate of their missing loved ones. In reality, Miriam knew very little. But the worst thing about that day was Dan, who never left her side and offered her his help at every moment.

I was consumed by hate. I won’t let her do this, I thought to myself. She will not take my place. I was already planning the cruelest prank I could possibly imagine: I would steal away her purple teddy bear, this strange friend of hers that she apparently loved with all her heart. Maybe she’d gotten it from her parents.

The day passed slowly. I tried to stay away from every-body—most of all from her. I found comfort in working out the smallest details of my plan—without saying a word about it to anyone else, of course.

That night, when we climbed into our beds, I waited for everyone else to fall asleep. Then, I approached her bed. Like me, she was still awake and seemed worried. As always, she was ready to run. Even in the darkness, I noticed the flicker of fear in her eyes as she saw me coming closer. The teddy bear was clutched tightly in her arms. I grabbed it with force. Not immediately understanding my malicious intentions, she stayed put. But soon, she figured out what I was up to and panicked. Tears shone in her eyes. She jumped off her bed and leapt toward her teddy bear to grab it back. So I pulled it toward me—and she pulled it toward her. A few seconds later, the faded cloth tore, and the bear’s insides—chunks of sponge and moldy rags—scattered at the foot of the bed. Seeing this, I defiantly tossed away the teddy bear’s leg, which I’d still had in my hand. With an evil smile on my lips, I walked back to my bed, my back straight and tall. “That should teach her a lesson,” I whispered to myself.

I curled up in my blanket. In the night’s silence, I heard her muffled crying as she gathered up the pieces, making sure not to lose a single one, as if she were collecting a set of precious pearls. When she finally finished, she went back to bed. Her soft sobbing continued for a while longer, and suddenly it gave me the most awful feeling.

Chapter 3

At dawn, Leah came in to wake everyone up.

“Good morning,” she said cheerfully, moving from bed to bed, smiling and helping us out of our blankets. She walked over to Miriam’s bed. Miriam’s eyes were furious—thundering, even. Leah looked around, and her gaze fell on the shredded teddy bear. She was astonished but said nothing. The two of them looked at each other.

Their silence said more than words ever could.

Leah was born in Poland as well, and she too probably came to Israel as a child. But this hadn’t been during the war, she once told us, so she hadn’t suffered or lived through the same horrors that many of the other members had.

They whispered to each other. Leah promised Miriam she’d sew it up. She even promised her a brand-new teddy bear, and she hugged the gaunt little girl. The rage in her eyes died down. Miriam felt safe in Leah’s warm arms.

Suddenly, Leah snapped up and asked, “Alright, children, who’s the big hero?” Her tone was angry with a touch of mockery. No one answered.

“Who tore up the teddy bear?” Leah asked, growing angrier. I was sure everyone knew it was me, but no one said a word. That was how we were at the kibbutz: we didn’t rat on each other!

“What teddy bear?” asked Yael, feigning innocence. We all went silent again. No one made a sound. And then Dan raised his hand. We were all stunned. I was overcome with worry. Dan’s hand held up high made me anxious. Would he tell on me?

Leah turned to him and asked, “Yes, Dan?”

“No … nothing,” he said, awkwardly.

I let out a sigh of relief. But my joy did not last long.

Leah asked again, this time quieter, “Who did this?”

Getting no answers out of us once more, she called me over, to my astonishment, while rushing the others off to the washroom. Everybody else left. Yael winked at me and disappeared as well.

Miriam sat on her bed and looked at Leah helplessly.

Dan walked over to her. He tried to gesture something to her with his hands and wound up looking pretty silly. I did my best to hide the smile on my lips, but I couldn’t quite do it. Where I failed, he succeeded by shooting an angry glance at me that froze the smile on my face.

After failing miserably at sign language, Dan took Miriam by the hand and together they marched off to the washroom. Leah followed them with her eyes, a kind smile spreading on her lips.

The preaching I received on how a leader like me should put more effort in to welcoming a new kid was not as bad as I expected. Much worse was what happened with the others after they had left. After Leah scolded me, I walked down to the dining hall. I sat in the middle of the bench, where none of the other girls from my class dared to sit, and Yael told me all about what happened in the washroom.

When the new couple reached the communal washroom, Dvora and Rachel, the women in charge there, were alarmed by the sight of the neglected girl and stared at her in wonder while the other children hurried off to stand in line for one of the three bathrooms stalls.

> When they were done, they quickly grabbed their toothbrushes, their toothpaste, and their personal towels and rushed to stand in line for the sink. Dvora whispered in Rachel’s ear. We heard fragments of their conversation—said Yael—words like “over there,” “new,” and “alone.” Then, Dvora walked over to the cupboard and pulled out a toothbrush and a fresh, clean towel. She turned to the girl, who seemed frightened by the commotion around her, and handed her the toiletries. The girl recoiled and seemed to be looking for a way out. Dvora, who was impatient that morning, gave up immediately and passed the task on to Rachel. Rachel walked up to Miriam, a motherly smile on her face. She tried to complete the task Dvora had abandoned, and she was indeed successful. Miriam took what was offered to her with shaking hands. Her voice was filled with wonder and hoarse with excitement as she blurted out, “Moje?” (Mine?) Dan tried to decipher the meaning of the word. “It’s probably Polish,” he said to Dvora, who nodded.

Dan led Miriam to the sink and showed her how to use the toothbrush and toothpaste she’d just received. Rachel, who noticed the bond of friendship forming between the two of them, sent them to the storage room to get Miriam her new clothes. The two left the washroom holding hands.

I was fuming as Yael told her story. I listened closely, trying to extract even the tiniest detail that may have slipped her mind. In the background, I could hear the boys’ table growing increasingly noisy as they began singing songs and cheering each other on. It was strange, but the girls’ table always seemed so much quieter, most of us preferring simple chatter and gossip to rowdy behavior. The boys, on the other hand, were wilder, often dancing and joking around. In fact, the only time we ever invited a boy to our table was if he had some new bit of gossip to share with us; stories about a couple caught out in the orchard, for instance, a new illegal immigrant, or some other interesting news. They were known as “the gang.” I looked over at their table. Dan’s seat was empty, and Rami and Doron were gone too. I looked around for Dan, and suddenly noticed Rami and Doron standing in the doorway.

The Girl From Over There

The Girl From Over There